Paint and Mortar Analysis at Prescot Picture House

Introduction

M Womersleys were instructed by the Major Development Team at Knowsley Council to provide a Paint and Render Analysis Survey for 8-14 Kemble Street, Prescot. Based upon taking samples externally from the front elevation (facing onto Kemble Street) and taking paint and plaster samples internally in the main auditorium area and at the mezzanine level, including from internal walls, decorative features, and from the fibrous plaster ceiling. This initial number of samples provided some answers about the likely decorative colour schemes, but also raised many more questions about the interior’s previous design, and more paint samples were taken and an analysis of them are also included within this report.

The interpretation of the results set out below, illustrated which renders and plasters were used to clothe the building, and which paint finishes decorated the Picture House in its hey days. These are based upon the samples taken and the historic context of this building, but with unfortunately very limited archival material, it will not be possible to date the various coloured layers with any accuracy.

The renders and paint finishes to the front elevation of the picture house and adjacent shops and the story they tell.

It appears from looking at both the render composition and the number of paint layers applied to the surface of the samples, that the original flat rendered areas may be comprised of a hydraulic lime or natural cement render. With the original decorative elements such as the run in situ panel moulding, being formed from an early OPC/Lime/Fine Sand mix. The planted on decorative elements, such as the swags, are likely to be the same build up as the scroll above the central bay of the main Picture House façade, which is comprised of almost neat cast early OPC. The use of a strong Portland cement mix was advised for cast external work from at least 1903,[1] and described in more detail by Millar, the decorative plaster specialist.[2]

We should not be surprised, as Picton describes how Roman Cement was first used in Liverpool as external plain rendered coatings to the front of buildings in about 1820,[3] and was used by Liverpool Corporation on their buildings from 1834,[4] with two Roman Cement dealers in Liverpool, listed in Gore’s Directory from 1834.[5] This natural cement appears to have arrived by ship into the port, and the author has come across other examples of its use in Liverpool, upto the late nineteenth century. Its use also extended to Lancaster in the same period, based on render analysis by the author at Lancaster Grand Theatre

We also know that more modern OPC had started to be produced in this region with 290,000 tonnes of cement clinker manufactured between 1907 – 1929 at Crosfield’s in nearby Warrington, (whose main business was soap manufacture).[6] Cement was also available from December 1912 from the Ship Canal Portland Cement Manufacturers Ltd., who produced 75 tons of cement clinker per day at the Ship Canal Works on Ellesmere port.[7]

Later cement-lime bound renders were used in repairing or renovating this building and can be seen in mortar samples, but it is unclear when they date from. Although in the late 1920’s it was not unusual for plain backing coats of cement render to be comprised of one part Portland cement to two parts of washed sand.[8]

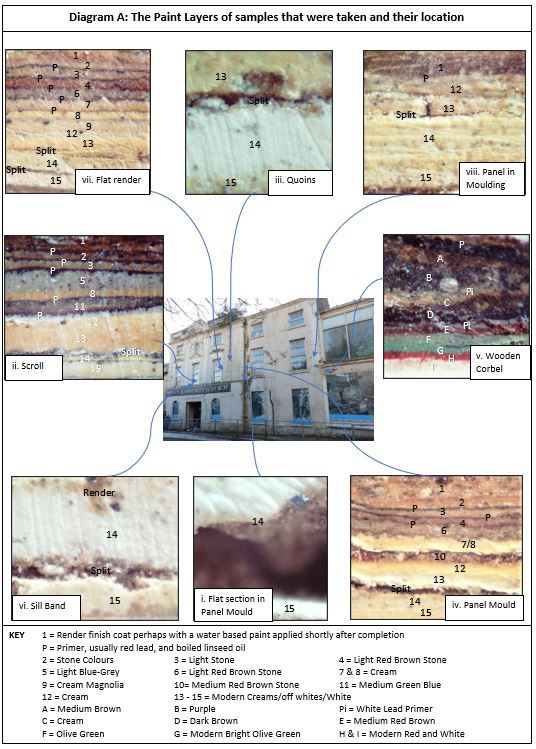

The areas of original rendered surfaces that remain, shown on diagram A, appear to have originally been coated with staining water based paints, as oil paints could not be applied within at least the first year to a new cement stucco.[9] Although, the red brown colour may also be from iron rich roman stucco or an iron rich lime-cement render. This has then later been followed with a priming coat, (references ‘P’ on Diagram A) of red lead and boiled linseed oil, [10] or of a combination of white and red lead, boiled oil, and turpentine.[11]

The next three coats may comprise of two undercoats, consisting of pigment carried in white and red lead, boiled oil and turpentine with some patent driers added, followed by a finish coat on flat rendered areas, which was tinted by pigments giving a medium stone brown-red colour. The panel moulding forming the edge pilasters seemed to use the same colour but some decorative details, such as the scroll, were apparently picked out in a lighter blue. This combination may represent the first full colour scheme, dating to within the first five years of the buildings opening. The flat areas then appear to have been coated in a subdued olive green.

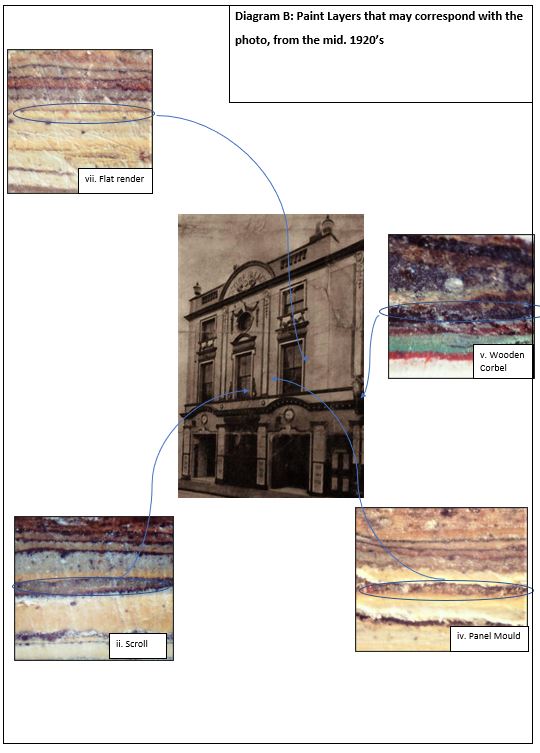

It appears from an advert for the Picture House, that may date to the early to mid-1920’s, based upon the telephone number ’39 Prescot’, shown on the flyer, that the next paint layers date to this period, and these are circled blue on diagram B below. They include a cream stone coloured plain render base, with the panel moulding to the pilaster details at the corners of the building and at the edge of the central projecting bay, being in a red brown colour, together with the corbel to the adjacent shop front. The decorative scrolls, and perhaps also the swags, being in an olive green colour.

After which all the wall areas and decorative details were coated in a bright cream colour, perhaps using Titanium Oxide based paints, which were mass produced after 1916,[12] and mentioned in decorating guides for some applications in 1938.[13] After this, the whole building appears to have been decorated in modern cream and white coloured paints.

The plasters and paint finishes used Inside the Bioscope and early picture house and the story they tell.

The wall and ceiling plasters, are what you would expect in the auditorium’s original construction, with a combination of sawn lath and lime plaster, gauged with gypsum just before use, above the proscenium arch, and also forming the proscenium’s flat beam ‘arch’. Lath and plaster is also found right at the back of the auditorium. The cast fibrous slightly curving plain ceiling panels, made up of plaster of Paris, hessian, and thin laths, decorated with fibrous gypsum plaster ribs and panel moulds and similar fibrous plaster decoration applied to the walls, may also date to the first constructional phase but could also be a little later, after a possible earlier lath and lime plaster barrel vaulted ceiling.

Some of the walls’ freeze bands retain original 1:1:6, cement-lime-sand plasters, used in this period,[1] and later earlier cement plasters below, later over skimmed with modern plasters, perhaps when the balconies were removed in the 1990’s to create an interior for a Pentecostal church. T

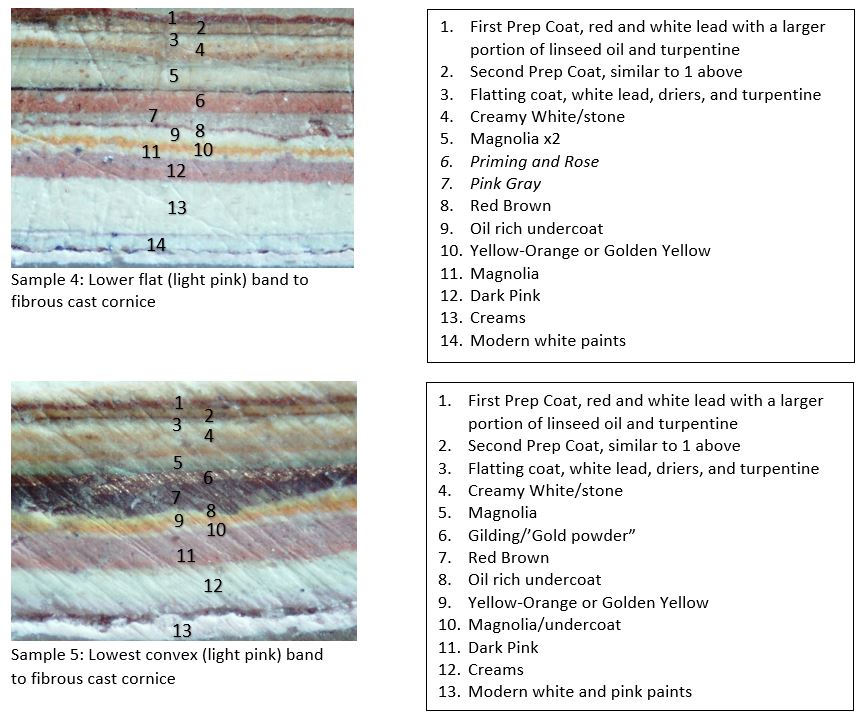

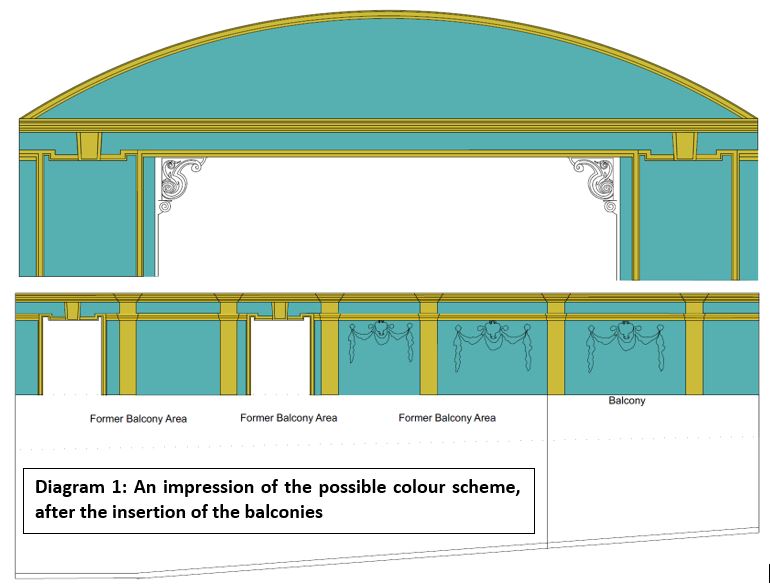

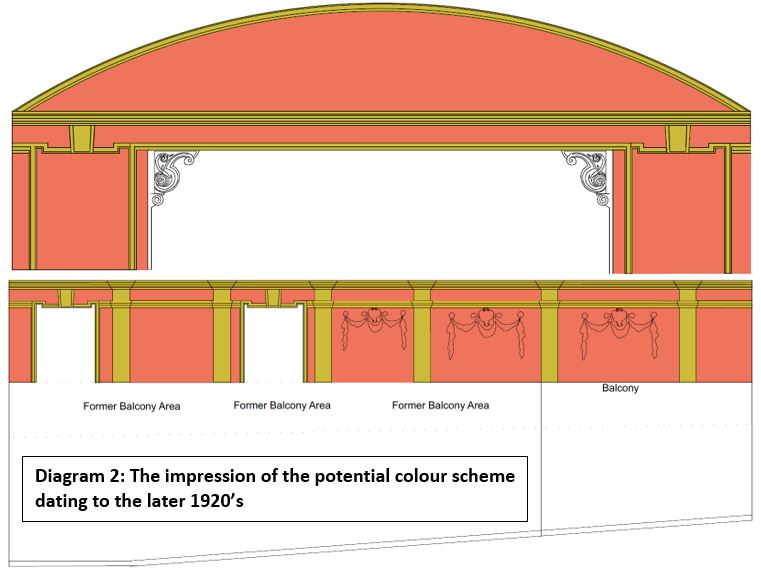

The plastered walls above the original balcony areas may have been painted in stone cream colours within the first period as a Bioscope Picture House cinema, as at the Majestic in Aberdeen, 1914.[2] In the second re-decoration period, after the insertion of new balconies in 1913, they were perhaps painted blue, with the pilasters picked out in stone, and the cornice, freeze band, and even perhaps the freeze itself painted in a finish of gold powder,[3] . After which the main wall below the freeze was coated in a strong rose colour. Later the areas immediately above and below the freeze bands are again painted both the same, with a golden orange colour being followed with a medium pink and then later more modern layers. An idea of the likely second decorative colour scheme, after the insertion of the balconies, and the possible third colour scheme from the later 1920’s, are illustrated on diagrams 1 and 2 below.

A similar combination of the second set of light blue, stone, and gold colours, perhaps dating to after the insertion of the balconies can be found at Coolidge Corner Theatre, Massachusetts which became a cinema in 1933,[4] and is illustrated in photo 1 below. The slightly later rose and stone colour combination found at Prescot Picture House could be seen at the Regent Centre In Christchurch, in 1936, five years after it was built, when it was given a plush makeover, featuring a deep rose, gold and silver colour scheme and art deco signage.[5] This decorative scheme has recently been recreated and is shown in diagram 2.

The ceiling colours, based upon the cross sections of paint samples, were light yellow green (almost blue) on the outer edges of the ceiling panels, with stone colours covering the main body of the panels as defined by the panel moulding, which may also have been decorated with the same stone colour. But as noted above, the ceiling plasters may not be original to the first construction phase.

The original paint colours and plaster below the level of the original balconies appear to be lost, although they could have been originally panelled. In the same way as the lower part of the auditorium walls at the Walton Vale Picture House (1922) and the Coliseum Cinema, Walton (1922) were covered by dark wood dados.[6]

The pilasters that divide the wall into bays were originally painted in a rose colour, over at least two decorative cycles and then later with stone colours. Perhaps originally standing out from the first cream/stone background colours, used in the main auditorium area before the insertion of the balconies. After which they were painted in as stone colour, although it is possible that they retained a rose colour above the level of the freeze band.

Analysis of additional paint samples would provide a more detailed picture of the auditorium’s appearance during the first 40 years of its life as a thriving cinema. However, it is clear that the early colour schemes sought to adopt the style of contemporary theatres to confer respectability and refinement.[7] Just before the Prescot Picture House opened it was described as “going to present a very palatial appearance”,[8] and from the paint analysis the Picture House owners appear to have achieved this.

[1] Mitchell, 35–35.

[2] William Millar, Plastering Plain & Decorative, 4th ed. (London: B. T. Batsford, 1927).

[3] Sir James Allanson PICTON, ‘The Architectural History of LiverpoPhool ... Papers Read Before the Liverpool Architectural and Archæological Society’ (The Liverpool Architectural and Archæological Society, 1858), 61.

[4] J. and J. Mawdsley, ‘The Account of the Corporation of Liverpool, with Their Treasurer from the 18th of October 1832 (to the 31st of August, 1834).’ (Liverpool Corporation, 1834).

[5] ‘Gore’s Directory of Liverpool and Its Environs for the Year’ (Gore’s Directory Liverpool, 1834).

[6] Dylan Moore, ‘Cement Kilns: Crosfields’, Private, Crosfield’s (blog), Dylan Moore: commenced /12/2010: last edit 18/03/2022 2010, https://www.cementkilns.co.uk/cement_kiln_crosfield.html.

[7] Dylan Moore, ‘Cement Kilns: Ellesmere Port’, Private, Ellesmere Port (blog), Dylan Moore: commenced /12/2010: last edit 18/03/2022 2010, https://www.cementkilns.co.uk/cement_kiln_ellesmere.html.

[8] Charles F. Mitchell, Building Construction. Advanced and Honours, 4th ed. (London: B. T. Batsford, 1903), 37–38.

[9] John P. Parry, Painting and Decorating - A Comprehensive Manual for the Craftsman with a Glossary to Technical Terms, Paper back reprint of 1938 original (Porter Press, 2012), 67.

[10] Parry, 67.

[11] Walter Pearce, Painting and Decorating (London: Chas Griffin & Co. Ltd., 1898), 114–15.

[12] Kassia St Clair, The Secret Lives of Colour (London: John Murray, 2016), 40.

[13] Parry, Painting and Decorating - A Comprehensive Manual for the Craftsman with a Glossary to Technical Terms.

[1] Mitchell, Building Construction. Advanced and Honours, 46–48.

[2] David A Ellis, ‘Majestic Aberdeen’, Cinema Theatre Association - Bulletin, December 2022.

[3] Ian C. Bristow, Interior House-Painting Colours and Technology 1615-1840 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996), 140.

[4] Time Out editors, ‘The 50 Most Beautiful Cinemas in the World: Planet Earth’s Most Heavenly Picture Palaces and Movie Houses’, 26 February 2021, https://www.timeout.com/film/the-50-most-beautiful-cinemas-in-the-world.

[5] Harriet Sherwood, ‘Dorset’s Art Deco Cinema Jewel Returns to Its 1930’s Spendour’, The Guardian Online, 25 October 2020.

[6] Harold Ackroyd, Picture Palaces of Liverpool (Liverpool: The Bluecoat Press, 2002), 99-100.

[7] Gomes Maryann, The Picture House. A Photographic Album of Film and Cinema in Greater Manchester, Lancashire, Cheshire, and Merseyside from the Collections of the Northwest Film Archive. (Manchester: Northwest Film Archive, Manchester Polytechnic, 1988), 22.

[8] Bioscope Correspondent, ‘In The Liverpool District’, The Bioscope, 18 July 1912.

Related Articles

The steps members of the Waterton’s Wall restoration team, with support from Mark Womersley, have been following to consolidate, conserve and repair this historic wall that represents the successful efforts of Charles Waterton to preserve the wildlife that lived on his estate near Wakefield in West Yorkshire.

1. Fill deep voids behind the wall’s facing stones with deep pointing work. The works involve …

Mark spent a day recording a historic timber-framed garden building at Woodsome Hall

Mark Womersley, as part of his voluntary work with the Yorkshire Vernacular Buildings Study Group, spent…

M Womersleys were delighted to offer a day of tutoring to those who attended the Wentworth Woodhouse Working Party

M Womersleys were delighted to offer a day of tutoring to those who attended the Wentworth Woodhouse…